Remembering Rod Paige

“No child should have their future determined by their zip code…”

“No child should have their future determined by their zip code…”

Yes—that was Rod Paige. And it was 2003.

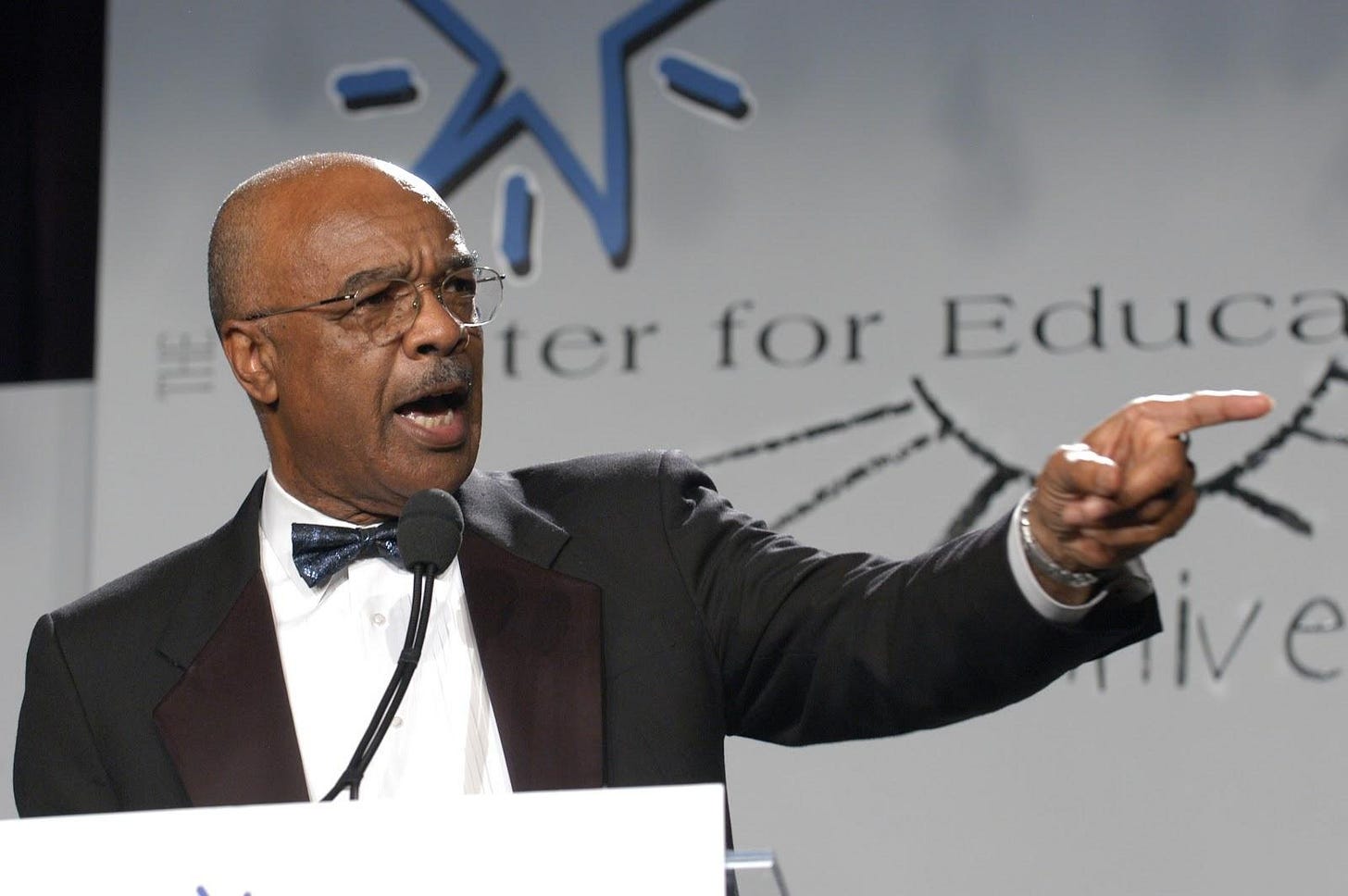

In fact, it was at the Center for Education Reform’s 10th anniversary when we honored Secretary Paige that he helped cement what has since become that near-sacred principle of education policy—one we now take for granted: that money should follow the child, not the other way around.

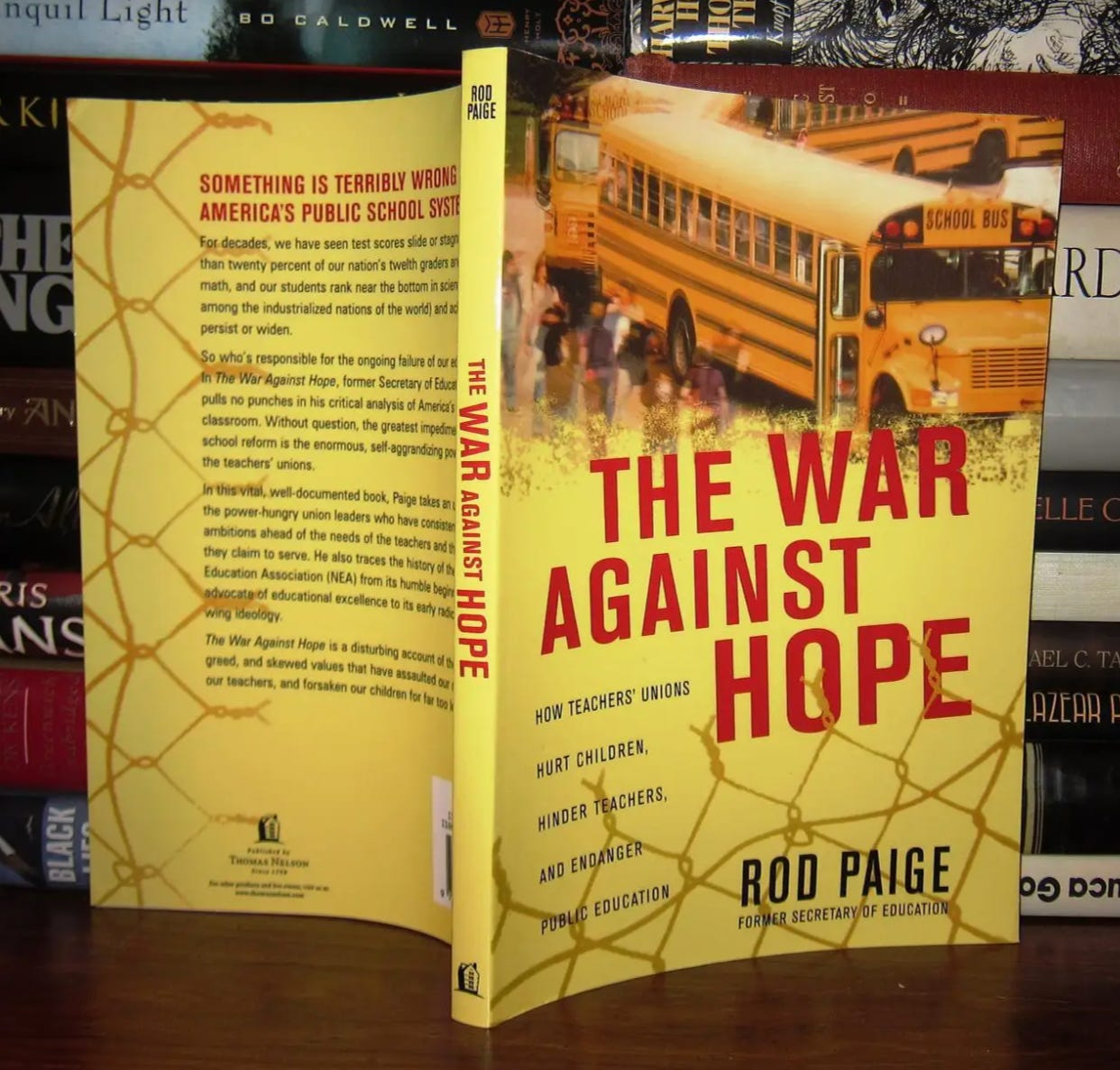

A few years later—now twenty years ago—Rod Paige left the traditional education world aghast by publishing a book whose subtitle said exactly what few people in public life were willing to talk about: “How Teachers’ Unions Hurt Children, Hinder Teachers, and Endanger Public Education.”

Once taboo and dismissed in all but policy circles, this truth is now fodder for kitchen table conversation, spurring a new generation of educators and parents starting their own schools, making his book even more indispensable to families nationwide.

I remain deeply flattered that he attributes part of his decision to speak plainly—and publicly—to an exchange we had years before. In The War Against Hope, Paige recounts the moment when our paths first crossed—an exchange he chose to place at the very front of his book. He describes a packed Milken National Education Conference, a panel of distinguished experts, and a wide-ranging discussion about teacher quality. As the session drew to a close, one final question was allowed. He recounts my question in his book’s preface, The Elephant in the Room:

I am Jeanne Allen from the Center for Education Reform. You’ve all provided an incredible amount of depth and breadth to both the problems and the solutions, and I commend you for doing it really comprehensively. But with all due respect, Lowell, there’s an elephant in the room that hasn’t been mentioned.

Before the 1960s, there were associations that supported, defended, and held to high expectations educators all across the country. Somewhere in the 1960s there was a transition where those associations stopped coming to the fore and actually became professional unions. Now they’re just unions, not even professional, as some would argue.

What happened? Where is that in the discussion?

He says the room went silent. He responded, and later writes:

The behavior of the big, all-powerful teachers’ unions is unquestionably the most significant determinant of the success or failure of most education reform efforts. But we had just spent two hours discussing education reform without even mentioning them. That in itself is a major statement about where we are in terms of improving America’s system of education.

Why don’t we talk more openly about teachers’ unions and their influence? Why do we avoid speaking honestly about what they do (or don’t do) to influence school reform efforts, and what they need to do differently? One possible explanation is that we have come to accept their actions against reform as inevitable—as a fact of life. But another logical reason for this absence of discussion is that the nation isn’t fully aware of the destructive impact that many teachers’ unions are having on the education of America’s children.

The conversation that day made me realize more than ever just how urgently this book is needed, and I redoubled my efforts to finish writing it. I wanted to shine a bright light on teachers’ union behavior and increase the probability that, in conferences such as the one I just described, we can begin to openly discuss and debate the influence of these massive organizations and consider how they must change in order to support and spur reform in our public education system.

This book should be required reading for anyone involved in education policy today and among all parents—especially because it validates their advocacy, underscores the importance of what they have learned the hard way, the longevity of the issue.

Rod Paige knew that because of the unions, merit gives way to uniformity, excellence is treated as inequity, and teachers themselves are shortchanged while unions grow richer, more political, and further removed from classrooms.

He also once famously stated to reporters—to huge outcries— that the National Education Association (NEA) was a terrorist organization. He was making a statement about their use of intimidation, coercion, and fear to block reforms aimed at helping America’s most vulnerable students. He wasn’t wrong.

Paige spoke not as a political actor, but as someone who had lived every level of the system: teacher, coach, principal, superintendent, and ultimately Secretary of Education.

Why would someone so prominent take such a risk, to absorb personal and political cost?

Because Dr. Roderick R. Paige was a principled leader. Born in Monticello, Mississippi—the son of a public-school principal and a librarian—education was not an abstract policy concern for him; it was a lived inheritance. After earning degrees from Jackson State University and Indiana University, Paige began his career in the reality of classrooms, on athletic fields, and in schools that served communities with substantial challenges.

He went on to serve as dean of the College of Education at Texas Southern University, where he founded the Center for Excellence in Urban Education—work that helped shape national conversations about instructional quality and school leadership. As superintendent of the Houston Independent School District, Paige led reforms that became known as the “Houston Miracle,” decentralizing authority, strengthening literacy instruction, expanding charter options, and tying leadership performance to student achievement.

In 2001, Paige was confirmed as the seventh U.S. Secretary of Education becoming both the first former superintendent and the first African American to hold the post.

Secretary Paige was in a Sarasota, Florida classroom with President George W. Bush when the Twin Towers were hit.

Perhaps that’s what gave him the additional firepower to fight, to not take anything for granted. Even as the nation was still reeling from its most vicious attack and searching for renewal and resolve, he oversaw the implementation of the most ambitious overhaul of federal education law in modern history—No Child Left Behind—designed to bring higher expectations for students, real accountability to systems, meaningful support to teachers, and greater agency to parents.

That NCLB is commonly dismissed as a failure is a subject for another essay. It wasn’t. It was sabotaged—by forces unwilling to use transparency and accountability to deliver better education. Today’s bipartisan embrace of the Science of Reading traces directly back to NCLB, as does the insistence that parents must be respected, outcomes matter and that children cannot be endlessly excused into oblivion.

Despite leading one of the nation’s largest urban districts, Paige was also an early and unapologetic champion of education choice—long before it was fashionable. (It was cool then, too—just not “super cool.”) He listened—to rank-and-file educators, parents, and advocates—and repeated often that education is a civil right, and where a child is born should not determine what that child can become.

His refusal to look away helped inspire not just his continued work over time but a movement of millions of parents and teachers who knew something was wrong but had been told not to say so.

We still wallow in low expectations.

Which raises the question we should be asking now—aside from the obvious success of increased opportunities and innovation throughout the whole of U.S. education, where has the public fire gone to distinguish that soft bigotry of low expectations, that seemingly unapologetic action of zoning children by zip code and frankly, declaring victory over a paltry two- to three point achievement gains when we’re dozens from excellence?

Friends—it’s a New Year. Together, advocates from vastly different backgrounds and sectors have forged millions of new meaningful education opportunities for students. But it’s not enough.

Dedicated public officials like the late Rod Paige helped to set the stage for an increasing number of leaders who stand with students and parents over bureaucracy. And yet, it’s cyclical and they are still far too few.

The solution? The best path for the cause of freedom and for the future of our country is to remember people like Rod Paige, understand the history of where we’ve been so we can chart where we are going, and to seek to rekindle in ourselves the drive, courage, and perseverance people like him embody wherever they go.

He was, as colleagues said upon his passing, unsatisfied with the status quo. Are you?

Rod devoted his life to ensuring that where a child is born does not determine whether that child can succeed.

And whether you knew him, or ever heard of him, that should be our charge. Requiescat in pace, dear friend.

Throwback

Okay so in the midst of doing research for this piece, I came across this crazy 2002 video from a US Department of Education–sponsored town hall convened under Secretary Rod Paige and led by then–Deputy Secretary Gene Hickok. It’s a striking reminder not just about my great hair and youth once upon a time 😎 but of how long the debates over school choice, parent power, and accountability have been underway. Watching this now feels like a time capsule: substantive, thoughtful, and a little like deja vu all over again.

Even at a U.S. Department of Education that has since proven its limits—and is now in the midst of being dismantled—it’s a reminder that leadership from Washington still matters. Today’s 13th, and potentially last, Education Secretary, Linda McMahon, is following a path Rod Paige carved nobly: talking to and visiting with the people who matter most, saying the hard things repeatedly, and leading boldly. That is what shapes culture over time.

I’m in the midst of finishing my second book and am channeling the extraordinary examples I’ve had the privilege to learn from over these many years. I’ll be back soon, time permitting. Happy New Year, and may God bless America—especially in this all-important year. -Jeanne